THE TECHNOLOGY THAT MADE THE VICTORY POSSIBLE – RADAR

During the1920s and 1930s, scientists worked on ways of detecting aircraft from far away, long before they could be seen by people on the ground. The First World War – or Great War as it was then known – had used aircraft for light bombing raids and, with the advancements that had been made to aircraft, it was felt that a serious air attack was a real possibility in the future.

The Air Ministry set up the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence in 1934, and scientists including Robert Watson Watt, Arnold F Wilkins and Edward George Bowen tried out ways to create a detection system for incoming aircraft.

One of the favoured methods was using radio waves and, on 17 June 1935, radio waves as a way of spotting aircraft was first successfully demonstrated by the British scientists.

How Radar Worked

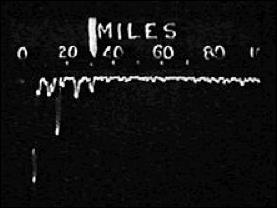

A radio wave was sent out. If it hit something, the signal or wave ‘bounced’ back, and so detection of a radio ‘echo’ indicated that something was coming towards the place where the wave was first sent. Waves were sent out a few times a second, and measurements were plotted on a screen to produce a display that looked like a straight line, rather than the circular image we associate with radar now.

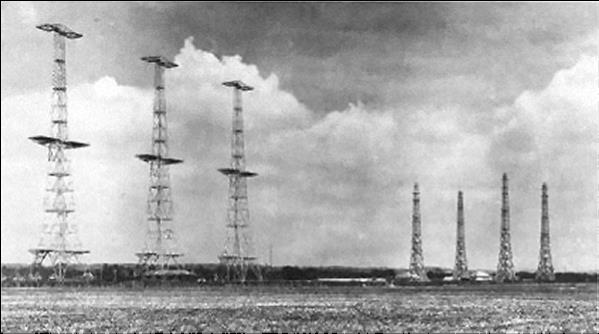

The radio waves were sent out by towers like the ones top right, and were set up all along the southern and eastern coasts of Britain.

The signal would be monitored by someone at a radar station, who would be able to work out how far away the flying object was and its speed. They might also very roughly be able to work out how many things were flying. Sometimes mistakes were made, and flocks of birds would be detected; however, their speed usually indicated what they were. Throughout the war, and during the Battle of Britain, many of those working in the radar receiver room on the RAF stations were women – part of the WRAF.

Towards the end of 1936, a linked early radar warning system was built along the British coast, known as Chain Home (CH). From 1939, there was also Chain Home Low (CHL), which was able to detect low-flying aircraft. Combined with spotter stations (people on the coast with binoculars), this provided the British with an important early warning technique for an air attack.

Although the technology was revolutionary at the time, the system could only look out to sea. Once the German aircraft crossed over the British coast and on to land, it was up to the spotters and other RAF stations belonging to the Observer Corps to monitor and plot the attackers’ journeys.

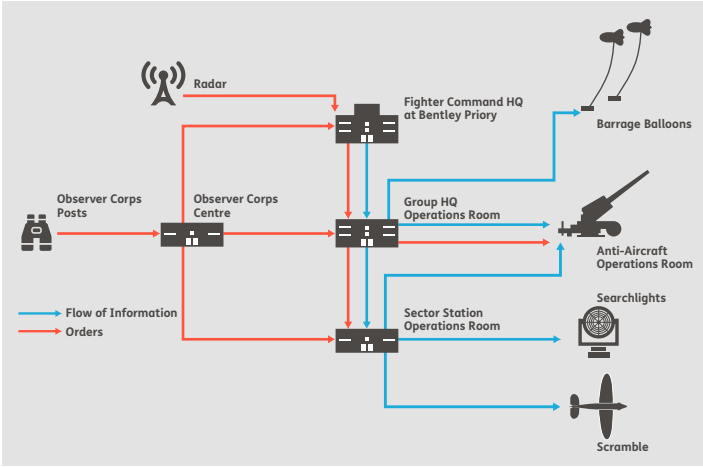

From Radar To Scramble

Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, Commander-in-Chief of RAF Fighter Command, created a reporting and responding system that ensured that the radar early warning system was as effective as possible. The Dowding system divided the UK into groups and sectors, organising a reporting structure for all the information collected that could be acted on with sufficient speed, so that any attack could be met with a British fighter response. All information collected at the radar stations was checked and then sent through to the headquarters of Fighter Command at Bentley Priory (near Harrow, North London), where Dowding had his own HQ.

A central part of the system was that the whole country

was divided into four groups (10 to 13).

- 10 Group, covering South West England and Wales under Air Vice-Marshal Sir Quintin Brand. Operational headquarters were located at RAF Rudloe Manor near Corsham in Wiltshire.

- 11 Group, covering London and the South East under Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park. Operational headquarters were located in Uxbridge, West London (now the Battle of Britain Bunker and shown in the film).

- 12 Group, covering the Midlands, East Anglia and parts of northern England under Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Operational headquarters were located at RAF Hucknall in Nottinghamshire during the Battle of Britain, and then moved to RAF Watnall, also in Nottinghamshire.

- 13 Group, covering the rest of northern England, the south of Scotland and Northern Ireland under Air Vice-Marshal Richard Saul. Operational headquarters were located in Kenton near Newcastle upon Tyne.

Bentley Priory would send the radar information to the appropriate group’s operational headquarters.

Each group was divided into sectors located across the area. The sectors contained the airfields, anti-aircraft guns and other defences such as barrage balloons. It was the responsibility of the operational headquarters of each group to organise the response to the enemy aircraft coming over their area, using the relevant sectors.

During the Battle of Britain, 11 Group was the busiest, as the German attack came across the English Channel and on to the south-east coast. As this was the time before computers, each of the decisions was made and passed on through the telephone systems, and every action was plotted on a large map in the Operations Rooms.

The whole process, from a radar operator detecting aircraft and telephoning the findings through to Bentley Priory, who checked the information against other sources, passing the information on to the correct group, to a duty Commanding Officer deciding how each of the sectors should respond, and Operations team and Sector team co-ordinating the response, had to be done in approximately four minutes!

This speed was crucial, as it took the German aircraft approximately 20 minutes after being detected crossing the English Channel to reach British targets in the South East. It took 14–16 minutes once a telephone call reached the airfield in the sectors to get the pilots into the British fighter aircraft, start the engines, take off (all called scramble) and fly towards the British coast to meet the German aircraft.

This meant that at no stage was there a second to spare if the Luftwaffe were going to be stopped from destroying British sites.The system worked very effectively, and all of the different people knew how to carry out their roles with the greatest efficiency. The combination of technological development and human planning and co-operation created a successful, modern system.